River’s traditional monsoon season never materialised

For the latest Cambodian Business news, visit Khmer Times Business

Typically this time of the year in the Mekong Basin, the annual monsoon is beginning to taper off, the mighty river’s banks are spilling over and saturating the flood plain in Cambodia and Vietnam and the river is moving millions of tonnes of sediment alongside of millions of tonnes of fish that migrate up and down the Mekong.

A total of 2.6 million tonness of those fish are caught each year and feed the people of the Mekong. But this year, the river from the Golden Triangle to the Mekong Delta is nearly dried up and those flows of sediment and fish are missing.

Despite two major storms that came from the South China Sea in August and caused severe flooding in southern Laos and northeast Thailand, the Mekong’s traditional monsoon season just never materialised. Normally the months of May through November bring a lot of rain to the Mekong Basin but this year, water levels above Vientiane in Laos were lower than normal dry season water levels.

Nearly all portions of the river are marking the lowest levels from the 1980s onward for this time of year. Some parts of the river hit historic lows for any time of the year.

In other words, during the monsoon season, parts of the river hit lows never seen before in the dry season.

Something is very wrong in the Mekong and these trends are continuing as mainland Southeast Asia now is fully transitioning, in a premature manner, into its dry season. This year’s dry season, which will run from now until April 2020 will likely be the lowest ever recorded and the region needs to prepare for extreme drought.

Nearly dry river bed

Activists and local peoples along the Thai/Lao border from the Golden Triangle to Nong Khai have been sharing photos on social media of nearly dry river bed from June to the present date.

The Tonle Sap Lake in Cambodia only received water from the Mekong mainstream for about six weeks before beginning to drain again. Typically it receives water for three to four months and this creates conditions for a 500,000 tonne fish catch from which Cambodians draw 70 percent of their protein. And, in the Mekong Delta, historic lows are preventing river water from keeping the sea tides out. This causes tidal flooding on a day to day basis in parts of the delta that have never flooded this way before. The Lower Mekong has hit a crisis point that will get worse and worse until the rains come again in May 2020 – and no one is yet sounding the alarm.

El Nino effect

The low levels are mostly caused by an El Nino weather patterns which is bringing much less rain to the Mekong than ever before. To the extent that the dry spell is the result of climate change requires more study, but climate change impacts are predicted to shorten the monsoon season and intensify the storms that do come during the monsoon season. That’s exactly what happened this year.

Perhaps early climate impacts are setting in, and it’s time to prepare for a new normal – or new abnormal.

Dams don’t help the situation unless they are releasing water to relieve drought and none of the Mekong dams are doing this to the extent necessary. They are simply not built for drought relief because they are single purpose hydropower dams. Each dam holds back water and sediment and fish migrations that affect downstream outcomes.

There are over 100 dams now operational in Mekong Basin in China, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam.

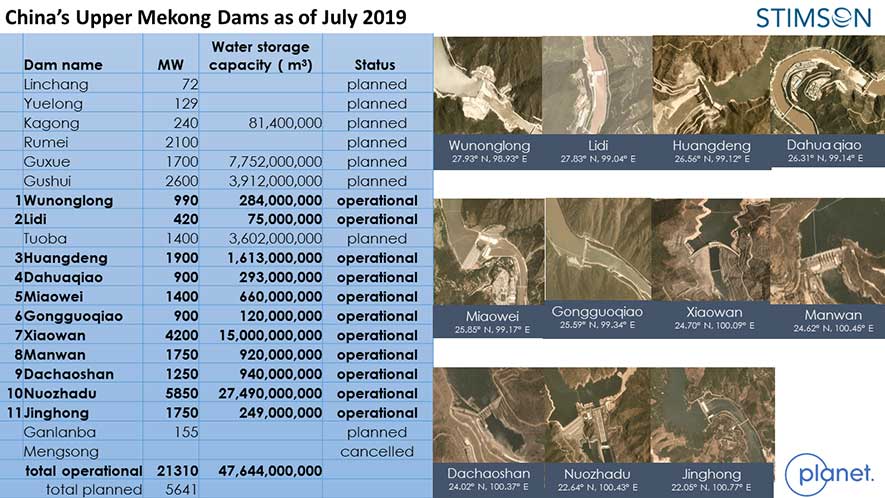

China, which provides the river with 40 percent of its water during the dry season, has completed eleven dams. These are some of the largest storage dams in the world.

Laos has completed 64 dams – the most in the basin – with 63 more under construction and could build hundreds more unless things change.

Cambodia has only two and is articulating a move away from its plans for Mekong dams, but the Lower Sesan 2 dam is predicted to reduce the total Mekong fish population by more than 9 percent.

Vietnam has sixteen and Thailand nine.

Together these are causing the Mekong to die a death of a thousand cuts when these dams, or some of them acting in a coordinated manner, actually could be used to relive drought. Yet no mechanism currently exists to relieve drought in the Mekong with dams.

Xayaburi dam and drought

The Xayaburi dam is a case in point. This summer when the drought really started to bite, the Xayaburi dam operators did some testing of turbines which actually exacerbated the drought to a degree in downstream areas.

My team proved this with satellite images that showed no changes to water level above the Xayaburi Dam in June but dropping river levels just below the dam throughout the same period.

During the worst time, the Xayaburi dam operators made the worst decision. Their denial that the dam did not affect drought is a flat out lie. And the lies and lack of coordination will persist until something forces a change to the way dams are operated.

The Tonle Sap is the world’s largest inland fishery and requires a full monsoon pulse to produce that fish catch. But this year’s fish catch will likely be severely reduced because the time for fish to enter the lake from upstream areas and grow many and grow large was about a fifth of the normal time.

The incubating effect of the Tonle Sap simply did not happen this year.

Also dams block the pathways of fish eggs and juveniles to be transported downstream from tributaries high in the system and into the Tonle Sap.

All fishing communities throughout the Mekong system are reporting extremely low fish catches this year. My team talked to fisher people along the Tonle Sap Lake who are reported a 70 percent reduction in fish catch for the month of October.

Relief plan needed

The entire region needs to come together and come up with a drought relief plan. El Nino effects can be predicted six months in advance so there’s no reason for the situation to be this bad. The lower countries need to sue China to guarantee minimum flow levels from its upstream dams and for China to help emulate natural flow patterns, especially during dire times like this which China is contributing much more than 40 percent of the river’s water.

Laos with its 60-plus dams needs to do this too especially if China is not responding. And the entire region just needs to prepare for longer dry seasons and more intense storms during the monsoons seasons. This means also that dams are increasingly becoming more part of the problem rather than part of the solution because dams will run at low efficiency during the extended dry season in addition to blocking the flows of water, sediment and fish migration through the basin. These countries are much better off looking to solar, wind, biomass, and natural gas to meet electricity demand.

No accurate predictions

There is no plan or blueprint for hydropower development in Laos. Projects are built out one at a time by foreign developers and investors who dictate next moves. This means that the government of Laos cannot coordinate between dams for water releases and such and it also means that the government of Laos knows not how many dams will be built by the time the damming stops decades from now. Unfortunately this also means we cannot predict with any kind of accuracy the degree of downstream effects on the Tonle Sap fishery or the agricultural productivity of the Mekong Delta. An anarchic situation of the worst kind is unfolding and it’s leading toward real crisis in mainland Southeast Asia.

Communities along the Mekong have long been suffering through these effects – lowered fish catches, irregular flows, and resettlement related to dams. But soon these effects will begin to bite in Mekong capitals and major metropolitan areas such as Ho Chi Minh City.

The fish won’t be showing up in markets and agricultural production especially in Cambodia and Vietnam’s Mekong Delta will suffer.

Rural refugees will arrive in cities faster than the cities can absorb them and, if a real food crisis happens, major refugee flows will move across borders.

Humans are extremely adaptable, so the region will adapt one way or the other. But growing pains will continue to hurt more and more as a result of these poorly thought-out plans for hydropower development and the climate effects to come.

Brian Eyler is the director of the Stimson Center’s Southeast Asia Programme and author of Last Days of the Mighty Mekong.