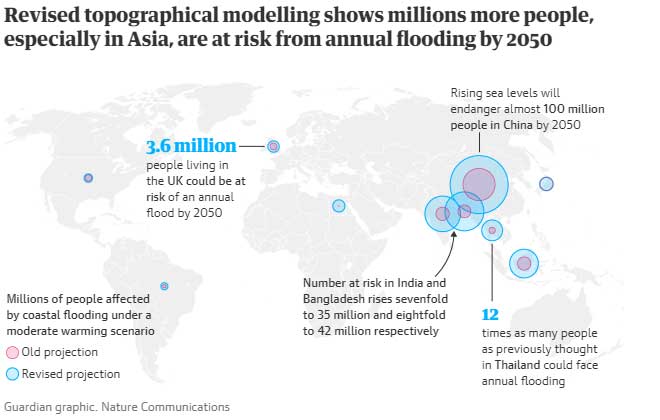

Figure is three times more than previously thought by expert observers

For the latest Cambodian Business news, visit Khmer Times Business

Cambodia could be savagely affected by a scientifically predicted rise in sea levels by 2050. New research by nonprofit news organisation Climate Central reveals that it will threaten land currently home to a total of 150 million people, mainly in south Vietnam and Thailand. However, there are fears that the Mekong delta will be severely affected with a knock-on effect for Cambodia and the risks associated with mass migration.

Climate Central concentrates on science. It is based in New Jersey and published in the journal Nature Communications. The sea level rise will affect three times more people by 2050 than previously thought. One future scenario described as moderate is that sea levels by then will submerge swathes of Southeast Asia.

According to the journal, sea levels rose between 11 to 16 centimetres in the twentieth century, driven by climate change. Even with sharp, immediate cuts to carbon emissions, they could rise another 0.5 metre this century. The report shows that, with higher emissions, this century could even bear witness to a rise in sea levels in excess of two metres in the case of early-onset Antarctic ice sheet melting.

Translating sea-level projections into the potential exposure of populations is critical for coastal planning and for assessing the benefits of climate mitigation, as well as the costs of failure to act, the report adds.

It says that land topography and elevation, as represented by what is known as Digital Elevation Models (DEMs), lie at the foundation of such predictions. High-accuracy DEMs derived from airborne lidar are freely available for the coastal United States, much of coastal Australia, and parts of Europe, but are lacking or unavailable in most of the rest of the world.

A lidar is a surveying method that measures distance to a target by illuminating the target with laser light and measuring the reflected light with a sensor. Differences in laser return times and wavelengths can then be used to make digital 3-D representations of the target.

A total of 360 million people globally are on land threatened by annual flood events in 2100 – an extra 110 million beyond previous thought, according to the study.

The researchers used a model that more accurately predicts land elevation than current models which often mistake the tops of trees for the ground. The reports reflects greenhouse gas emissions warming the Earth by 2 degrees Celsius and assumes a mostly stable Antarctic. Antarctic ice sheet instability may have a more profound effect.

Researchers said the magnitude of difference from previous US National Aeronautics and Space Administration study came as a shock. “These assessments show the potential of climate change to reshape cities, economies, coastlines and entire global regions within our lifetimes,” said Scott Kulp, the lead author of the study and a senior scientist at Climate Central.

“As the tideline rises higher than the ground people call home, nations will increasingly confront questions about whether, how much and how long coastal defences can protect them,” Kulp adds.

The reportsays the biggest change in estimates was in Asia, which is home to the majority of the world’s population. The numbers at risk of an annual flood by 2050 increased more than eightfold in Bangladesh, seven-fold in India, 12-fold in Thailand and three-fold in China.

According to the study, more than 70 percent of the total number of people worldwide currently living on implicated land are in eight Asian countries: China, Bangladesh, India, Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Japan,” according to the report.

It adds that the majority of people living on implicated land are in developing countries across Asia and chronic coastal flooding or permanent inundation threatens areas occupied by more than 10 percent of the current populations of nations including Bangladesh, Vietnam and many small island developing states (SIDS) by 2100.

More than 20 million people in the Southern Vietnam, almost one-quarter of the population, live on land that will be under water. Much of Ho Chi Minh City, the country’s economic centre, would vanish with it, according to the research.

Mey Kalyan, senior adviser to the Supreme National Economic Council, says that climate change is a big issue that will change everything.

“The damage from the climate change is serious. Currently, the source of water we consume is from the Mekong River. Climate Change could make the river shallow,” says Mey.

He also warns that the other risk to Cambodia is the rise in sea levels. He adds Cambodia’s land and rivers are low compared to the sea level. Therefore, any rise in sea level will affect Cambodia, especially in the lower Mekong delta.

Then salt water will flow into Takeo and Kampot provinces,” he adds. “One day, we will not be able to call the Tonle Sap a freshwater river but rather a salt water river. Therefore, the biodiversity will go crazy.”

Yin Savuth, director of the Department of Hydrology and River Works (DHRW) at the Ministry of Water Resources and Meteorology, agreed that there will be an impact because of the rise of sea levels.

“It will affect the areas that are close to the sea. Actually, when there is a rise in sea water it will have an impact.

Because this report is a prediction we have no idea how accurate it is but we are monitoring the situation carefully,” he adds.

“This year, some areas in Cambodia were flooded by the Mekong River, but some had low levels of water. In Vietnam, the Mekong delta, the water level is low, but in Laos the water level is high. Consequently, some provinces in Cambodia were flooded, such as Stung Treng, Kratie and Kampong Cham,” Savuth says.

“What we can do now is to monitor climate change and share information between the countries along the Mekong River and address issues to mitigate the risk caused by climate change.”

There is a need to strengthen evidence on the impact of rising sea-levels because initial evidence suggests that these effects could be higher than flood and storm damage. In this case responding to sea level rises is not sufficiently prioritised, according to a research paper titled Addressing Climate Change Impacts on Economic Growth in Cambodia that was released in early October by the Ministries of Economy and Finance and the Environment.

Ros Seilava, undersecretary of state at the Ministry of Economy and Finance, said Cambodia is among the most vulnerable countries to climate change in Southeast Asia, having limited institutional capacity to mitigate risks and adapt.

“This is a risk that could be detrimental to the pace of economic growth and sustainable development in the long run if we do not intensify our collective efforts,” said Mr Seilava.

He stressed that responses to climate change need to be interconnected and complementary among state institutions and development partners at both national and sub-national levels and require participation from the private sector.

According to studies by the Cambodian government, climate change will slow down Cambodia’s economic growth progressively over the next decades and delay the country’s graduation to a middle-income economy by one year, recent government reports show.

They say climate change will cause the Kingdom’s economy to grow at just 6.6 percent on average from 2017 to 2025, down from 6.9 to 7 percent if climate change was not a factor.

Climate change will reduce economic growth by 0.4 percent in 2020, by 2.5 percent in 2030 and by 9.8 percent in 2050. The researchers found that, if their predictions hold true, Cambodia will not become a middle-income economy until 2036, a year later than if climate change was not a factor. Tin Ponlok, secretary-general at the General Secretariat of the National Council for Sustainable Development, said investing in measures to respond to climate change could reduce loss and damage by a third. Mr Ponlok said the long-term solution is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere and to increase Cambodia’s resilience to climate change, particularly in agriculture, infrastructure, health, coastal areas and water management. “For 2018-2019, we need about $1.8 billion to take

immediate action on climate change,” Mr Ponlok said.

The reports also found that current adaptation activities underestimate the importance of heat stress on labour productivity and that more attention is needed to protect supply chains and workers from heat, particularly in farming, construction, and manufacturing. They recommend that more attention is paid to mechanisation, labour-efficient farming systems with flexible farm-work scheduling and improved working practices on construction sites.

In factories, the reports suggest that better ventilation, more drink breaks and more flexible schedules during heat waves can help combat the effects of climate change on the workforce. They also recommends the promotion of a better understanding of risk among workers and employers, better forecasting and measurement of heat waves and more planning to protect supply chains from heat stress.

Potential damage to assets from sea level rises is not strong, the researchers found, noting, however, that it could be more important than storm and flood damage.

Adaptation efforts could be doubled through a combination of an increase in labour productivity, measures to incentivise cost-effectiveness, and more international funding. The reports say this will reduce the adaptation gap to optimal levels.

More evidence is needed to improve the way adaptation policy is analysed to assess its effectiveness in protecting macroeconomic performance, the reports found. In particular, more work is required on comparing the timing of loss and damage threats and of adaptation benefits.