UN helps root out unsourced wood, persuade industry to branch out into sustainable work

For the latest Cambodian Business news, visit Khmer Times Business

The UN Development Programme’s innovative sustainable charcoal digital platform will help clamp down on unsourced wood and push communities to plant trees to supply kilns to produce the widely used reource.

Tech firm Okoone is behind the drive to promote sustainable production and consumption of charcoal to boost people’s living standards, says its technical director Florain Bacle.

The digital platform a complete ecosystem connecting a need for charcoal, with the production of sustainable charcoal from wood collectors, charcoal producers and delivery workers to its users.

Bacle says it also helps to track the wood collected even when offline, control the quota of wood, manage wood in stock, sell both wood and charcoal and understand the financial benefits of a sustainable charcoal industry.

“This platform also tracks the amount of charcoal produced, controls the quota of charcoal produced, manage charcoal in stock and sell the final product,” Bacle says.

An innovative digital platform to promote sustainable production and consumption of charcoal was developed by the UN Development Programme (UNDP) partnered with the Group for Environment, Renewable Energies and Solidarity (GERES), the Regional Community Forestry Training Centre (RECOFTC) and Okoone.

The project is called a “Sustainable Charcoal Production Digital Platform”. It provides a traceability system that captures the source of charcoal production, logistics and sales management in selected communities.

It also features an e-commerce function to improve efficiency in the entire value chain of charcoal, reduce transaction costs and make sustainable charcoal more accessible to users. This digital platform was successfully piloted in Pursat province.

In contrast with a traditionally non-sustainable, illegal and largely inefficient charcoal supply chain, the innovative digital platform will reduce forest degradation and greenhouse gas emissions, while encouraging plantation and forest restoration to support woodland communities, says Matthieu Albert, project manager of Kjuongo, an innovative social business concept to support the emergence of a sustainable charcoal value chain.

Albert says that the innovation for a sustainable charcoal value chain added value along the chain by ensured traceability and legality to access to wider markets, high quality charcoal and service and it has a positive social and environmental impact.

According to the UNDP, 77 percent of wood fuel for cooking and heating is from unsustainable sources. Two-thirds come from economic land concessions and agriculture and one-third is from overharvesting. According to the UNDP, wood fuel including firewood and charcoal is increasingly in demand in Cambodia.

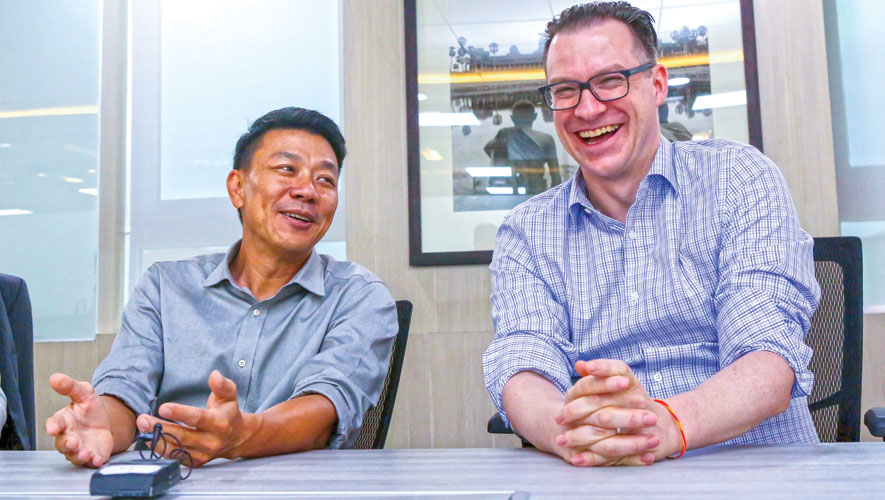

UNDP Resident Representative

About 800,000 tonnes of firewood is used in the garment and brick-making industry and 1.8 million tonnes for household cooking while 3.5 million tonnes of charcoal is used for cooking in households and restaurants. However, this growing demand for wood fuel is putting pressure on existing forests.

Growing demand

“At present, I work with the Group for Environment, Renewable Energies and Solidarity (GERES) to produce and supply the wood fuel to the market,” says Rin Sinuon, 55, one of the small-scale charcoal producers in Samrongyea village, Prangal commune, Kravanh district in Pursat province.

He adds that GERES has provided mobile phones, technical knowledge and equipment for producing charcoal and teaching how the system works. This provides another income to support the family.

Rin says that the digital platform can trace the source of wood fuel. He adds that it also connects community forestry groups to charcoal producers, charcoal cooperatives, charcoal distributors and users.

“With this digital platform, all the data from pre-production, during production and post-production of the charcoal, are recorded in the system, so it is clear to everyone in the chain,” Rin adds.

Rin, who has four charcoal kilns, has registered them in the system with GERES. He says that he can earn $3.60 for a sack (30 kilogrammes of charcoal) from GERES for his labour. Rin says that he just uses his labour and kilns, while, wood, facilities, equipment and other costs are shouldered by GERES.

“Each of my four kilns requires nine steres of wood to produce 30 sacks of charcoal – 960 kilogrammes of charcoal (one stere of wood is equal to a cubic metre). Each kiln will need from seven to 10 days to turn into charcoal,” Rin adds. “The technology is easy to operate because they teach us how to use it,” Rin says. “In my village, there are only two legal charcoal suppliers. The rest are not registered in the GERES system.” These, he says, are a substantial proportion.

UNDP Resident Representative Nick Beresford says that the digital platform promotes sustainable charcoal production and improves the livelihoods of communities who depend on charcoal production for their income.

Beresford added that wood fuel consists of firewood and charcoal. In Cambodia, wood fuel plays an important role in supporting rural communities as well as various industries and businesses.

For example, more than 80 percent of rural households rely on firewood or charcoal for daily cooking. Restaurants also use a large amount.

He added that firewood is also used in the garment and brick-making industries to generate energy.

According to GERES, the growing demand for wood fuel has added mounting pressure on existing forests. Most of the wood fuel is sourced from unsustainable origins. The total annual consumption of wood fuel now amounts to more than 6 million tonnes. This is equivalent to an annual loss of more than 71,600 hectares of deciduous forests.

“This is an alarming concern that needs to be addressed not only for the sake of the sustainability of forests but also for the wellbeing of humans,” a source, who declined to be named publicly, revealed.

“This digital platform builds on an e-commerce approach to improve efficiency in the entire value chains, to reduce transaction costs and to make sustainable charcoal more attractive and convenient to consumers,” said Mr Beresford.

He said that it introduces a mobile app for users and restaurants to be able to order sustainable charcoal to be delivered at their convenience. The platform also has a traceability system to ensure the sustainability of the entire value chain.

The government says to operate successfully, a legal perspective and framework to support the operation and facilitate the collection of forestry products to produce the wood fuel are needed.

The technical aspect is critical to inform charcoal producers how to calculate or convert one stere of wood to charcoal and know which types of wood can generate higher quality and amounts. In addition, it also separates the commercial side from household demand.

Keo Omaliss, the forestry administration director-general, said that sustainable charcoal production on the digital platform is important for the forestry community. It aims to create the production of wood fuel as demand increases. It is not only for use in Cambodia, but could also be available for export.

In the future, if we can check and evaluate wood fuel from legal sources, we can propose to the government its export. This would also provide income to communities.

“We try to push the legal charcoal to be more competitively priced compared with unsourced charcoal. If we cannot do that, it will be difficult to compete with unsourced wood fuel,” he added. “Legal timber cannot compete with illegal timber because legal timber producers pay taxes,” he added.

“Based on this recent successful experience, the FA [Forestry Administration] in partnership with GERES is scaling up its efforts in two provinces [Pursat and Kampong Chhnang]. Good practice and lessons learned will be used to inform the national government to improve policy promoting sustainable wood-fuel production and consumption in the future,” Omaliss said.

He also said that the purpose of this digital platform is to help to boost the living standards of the community by using sustainable charcoal.

“In the future, the government encourages them [the community] to export the charcoal if the production is not affecting forestry resources. “We can check on legal wood. We have the teams to check on logging in the forest, transportation and use in the charcoal kiln, as well as transport to the consumers, so we trace them all the way,” Mr Omaliss said.

“We are trying to transform the unsustainable wood industry to sustainable practices,” he said. “We cracked down on about 1,000 cases of illegal forest logging and transportation and, last year, we cracked down again on a big scale to drive the illegal deforestation down this year,” Mr Omaliss said.

“We have the mechanism to manage the forest, so the industry has to put into practice what is set out in the action plan, which was acknowledged by the Forest Administration office,” he said.

“Illegal forest logging to produce charcoal will affect wood which should be serving the next generation. Then we will have no forest to protect us from natural disasters. We want them to grow trees to produce the charcoal to avoid any effects on the natural forest,” he added.

Mr Beresford added that the UNDP wants to work with the government and community to build a more sustainable system.

“This is the way we are trying to do it,” he said “This technology is also good for the community. If they are protecting the forest in a sustainable way and as a source of production, they also win and they get a better price, a better reliable income. This way we can make it more a holistic, mutually beneficial system.”