Banks are finding it hard to let go of their love for the dollar

For the latest Cambodian Business news, visit Khmer Times Business

The National Bank of Cambodia has instituted a multi-pronged approach to incrementally push for more riel usage and ultimately be the arbiters of the Kingdom’s monetary policies.

A major part of the central bank’s initiative is to make financial institutions realise their role in promoting the riel and moving away from a dollarised loan portfolio. In 2016, the central bank announced that banks were required to meet a 10 percent riel quota in their loan portfolios by the end of 2019.

But a cursory survey of banks shows that most of the foreign banks are chafing under this deadline. Far from being complacent though, banks are actively coming up with creative financial products to incentivise local currency loans, especially those already disadvantaged by not having branches in provinces where riel usage is prevalent. To make it worse, there has never been a great demand for riel loans from commercial bank customers.

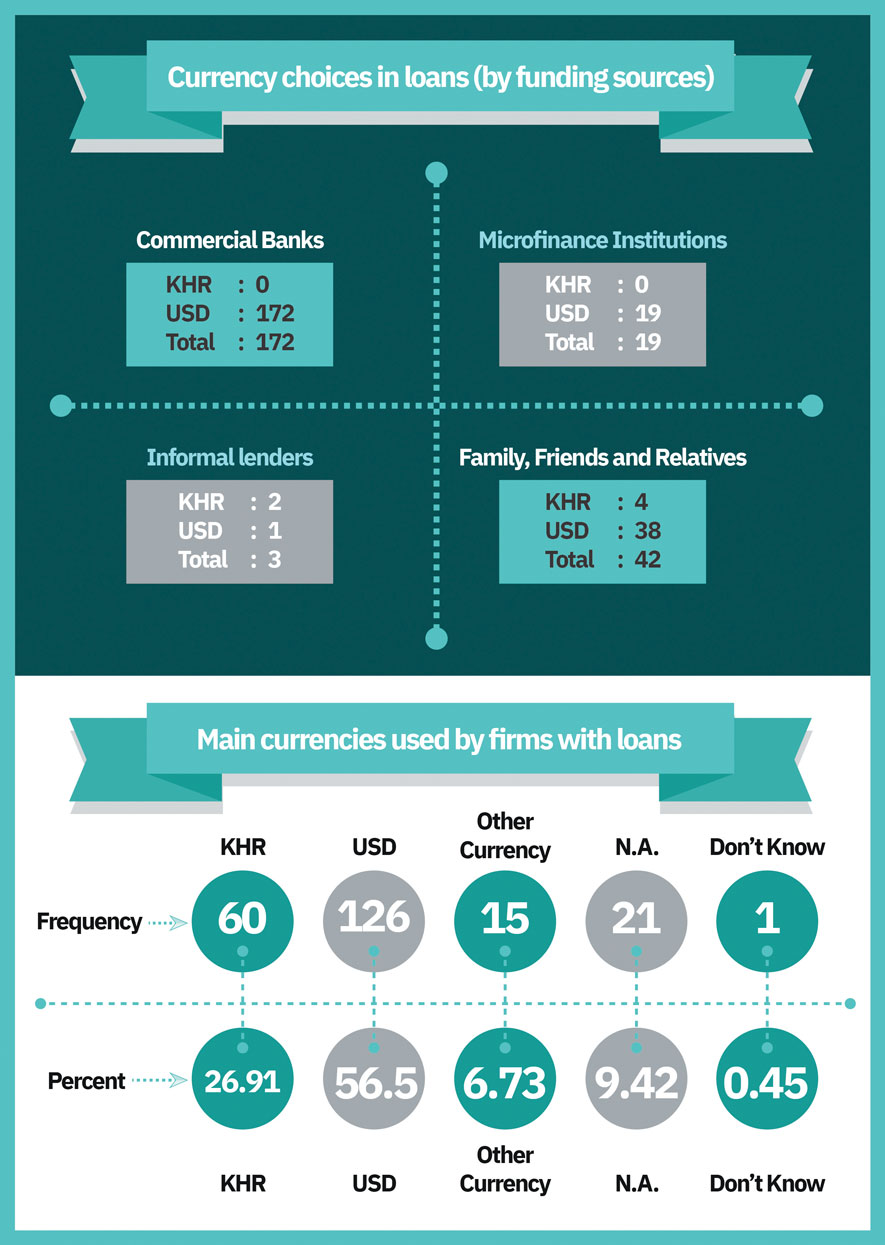

Conventional measurements used in the media from NBC and World Bank testify to this sentiment. The picture painted by their statistics shows a completely dollarised economy. The ratio of dollars deposited in commercial banks is as high as 98 percent while 95 percent of the loans are denominated in dollars.

Bank woes

On a warm day in February, people were chatting with tellers in hush tones inside the cooled glass building of the Phnon Penh Commercial Bank (PPCBank) headquarters on Norodom Blvd. Dollars were being pulled from trays, counted out slowly and stuffed in handbags.

“I think most of the bank find it difficult to meet the quota by its deadline. Especially those who have their strategic focus on corporate banking.”

“Demand on Riel loan comes mostly from households in provinces, which are MFI’s turf. We don’t want to disrupt their business and rather work as a financier to their operation. That is our strategy to meet the NBC guideline.”

“If I may make a suggestion to the NBC – it is pushing something that’s not in line with supply and demand,” he says.

“As for Khmer riel loans, we have customers who swap them into dollars after disbursement and that’s not the right move. I think the government needs to control the timeline. The bank itself should grow first, then only supply will automatically follow,” Shin adds.

He is not alone in voicing concerns over meeting the deadline. Most of the foreign commercial banks say they are around the five-percent range in their loan portfolios and are feeling the pressure to meet the year-end deadline.

Hong Leong Bank (Cambodia) PLC chief executive officer Joe Farrugia sympathised with his counterparts in the city.

“Most banks are finding it difficult to meet the 10 percent requirement,” he says. “(Although) we’re optimistic of meeting the target with a few new initiatives, realistically we will more than likely fall short, perhaps around seven percent,” he adds.

A significant number of banks will most likely be unable to meet the quota this year and there has been no real communication about the consequences for missing the deadline.

“At this stage there has been no indication of the penalties from NBC,” Farrugia says.

The central bank is like a parent and the banks are its children, a senior manager at a large commercial bank analyses.

“That’s a good way of looking at it. When your mom or dad tells you to do something, you really don’t want to be the kid who doesn’t do it,” she says.

Are deadlines necessary?

From the central bank’s point of view, the quota is necessary to reduce the dominance of the greenback while giving the local currency a fighting chance to be embraced in the Kingdom. But are there any risks in administrative decisions that could harm the Kingdom’s much lauded growth rate?

The answer is, no one really knows. This may explain the central bank’s reluctance to communicate penalties for not meeting the quota. It’s a delicate balancing act and some analysts say the act of setting a deadline could prove “heavy-handed”.

“One of the risks is that the policy measure could cause a reverse in financial development,” says Daiju Aiba, a research fellow with Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), which works closely with NBC, surveying the dollarisation of the economy.

“Actually, most financial institutions are dependent on US dollars, largely because funding costs are lower than riel. This environment makes it easier for financial institutions to operate in Cambodia especially for foreign-owned ones,” he says.

While no one argues the inevitability of de-dollarisation in the Kingdom, there has been much discussion if this is the right time for this kind of quota deadline. With generational economic growth in the economy, is now the best time to hinder bank lending with currency quotas?

“No one knows the best timing to set the deadline. From my perspective, setting a clear deadline is important to show NBC’s commitment to de-dollarise the economy. The country actually needs de-dollarisation to further develop its financial markets,” he opines.

Although, he admits, that without deadlines, banks might never change their lending habits.

Dollarisation origins

It is hard to imagine sometimes that the Kingdom is a generation away from a time when there was no widely circulating currency. It was a time where bartering was commonplace. Transactions were made using tobacco, jewellery, gold and even rice.

At the end of 1991, foreign exchange currency deposits in the Kingdom totalled only 0.005 percent of the gross domestic product. From 1991 to 1992, United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia brought in $1.7 billion, equivalent to 75 percent of the GDP. The dollars were spent mostly on housing rental fees and local services for peacekeeping operations. The volume of riel in Cambodia equalled less than a tenth of the US dollars that was pouring in, being spent in restaurants, bars, and hotels. It was at this point, dollarisation officially began, and people finally had a currency they could count on. Imagine the seismic shift of being a nation without a widely circulating currency that was suddenly inundated with greenbacks.

How long will it take?

Researchers and economists agree that the de-dollarisation of the economy and promotion of the riel will be a generational journey.

“In order to complete the de-dollarisation process, it will take a long time, like decades or something,” Aiba concedes.

However, he says, the complete de-dollarisation is not efficient because there is some benefit from using foreign currency.

“Even in developed countries, there is always a demand to hold foreign currencies as asset, and for transaction,” he adds.

In addition, the total domination of the dollar in the economy is somewhat overstated, especially when looking at macro studies. A nationwide survey conducted by the central bank and JICA Research Institute, revealed a more nuanced picture of currency usage among households, not just the financial sector.

“There are many households and enterprises that use riel daily. This is common in rural areas. The result also suggests that looking at the financial sector alone is misleading,” Aiba says.