Even without the removal of Everything but Arms, Cambodia’s economy is vulnerable to slowing garment, footwear and rice exports

For the latest Cambodian Business news, visit Khmer Times Business

After years of speedy expansion, the pace of Cambodia’s export-fuelled economic growth is set to slow from 2019 onwards, according to analysts. Further downside risk stems from the potential withdrawal of EBA trade preferences by the European Union. But even if access to EBA benefits is not removed, competition from lower cost and more efficient Asian rivals threatens to impact the growth of Cambodia’s garments industry, which make up the bulk of exports to the EU. Goods exports to EU member states make up about 20 percent of Cambodia’s total GDP. Withdrawal of EBA will hurt a major driver for Cambodia’s economic growth. Conversations with analysts and experts suggest that Cambodia faces a real risk of losing preferential trade benefits under the EBA, in the coming quarters.

Analysts at Fitch Solutions Macro Research believe the EU is hoping the threat of economic sanctions could force Prime Minister Hun Sen to pardon opposition leader Sam Rainsy, who fled Cambodia in 2015 to escape a slew of court convictions. That appears unlikely. On Dec 26, Hun Sen reportedly said he would arrest Rainsy if he returns to the Kingdom. In addition, Cambodia’s embrace of China as a major foreign investor and strategic partner appears to be a major – albeit unpublicised – reason for Western pressure, according to a source with direct knowledge of the ongoing Cambodia-EU negotiations on the EBA. It is believed that this may have key implications for Cambodia’s garment and footwear industry, where Chinese firms have a market share of over 50 percent.

If Cambodia’s EBA access is revoked- which is thought to be highly possible – the pressure on export growth will only intensify. This will present a challenge for Cambodia’s export-driven economy, which relies on Europe for a third of its export earnings. Ninety percent of Cambodia’s goods exports to the EU are sold through the EBA initiative. Cambodia’s textiles, clothing and footwear industry has been a major force behind the nation’s emergence as one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, contributing 1.4 percent to Cambodia’s average annual real GDP growth of 6.6 percent from 2012 to 2017, according to Moody’s Investor Service Inc. A withdrawal of EBA status for Cambodia would put “significant downside pressure” on Cambodia’s GDP growth, Fitch says. “There is little doubt that the garment industry, with its estimated 700,000 workforce and thin profit margins, will be the hardest hit,” says the group.

“Other countries such as Australia and Canada could follow the EU in reviewing their trade agreements with Cambodia, compounding the effect on exports,” says Matthew Circosta, a Singapore-based analyst at Moody’s.

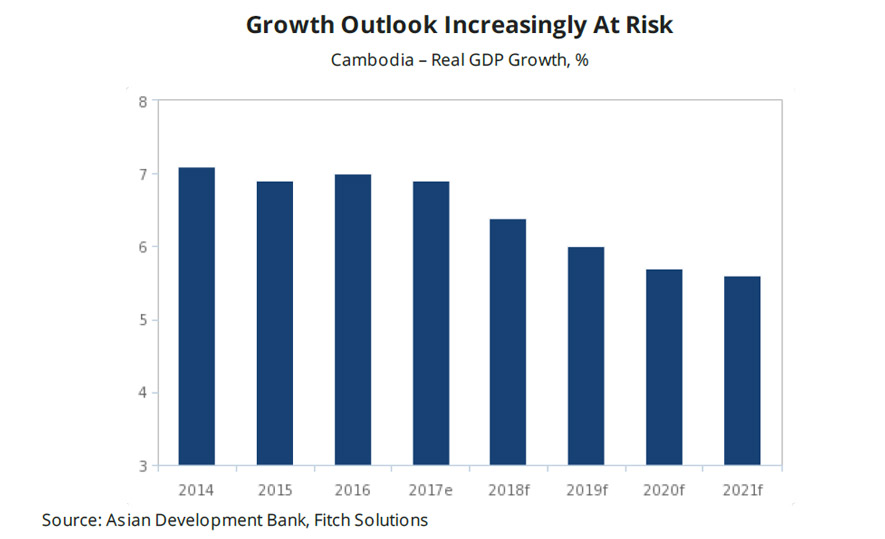

“Any negative effect on garment employment and wages would weigh on domestic demand, which has supported overall growth in Cambodia,” he says. But even if EBA benefits are not revoked, competition from lower-cost and more productive regional rivals is already hurting Cambodia’s garment industry. Export growth is also slated to slow down, as shown by International Monetary Fund forecasts. Without imputing the impact of EBA withdrawal, Fitch projects Cambodia’s GDP to grow at 5.9 percent in 2019. This would be the slowest growth rate for Cambodia since 2009, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Cambodia’s garment industry has long attracted global apparel brands like H&M and Zara through the widespread availability of low-cost labour, among the cheapest in the world. But this advantage is fast diminishing in the face of surging wages, warns Ken Loo, secretary-general of the Garment Manufacturers Association in Cambodia. By 2023, Cambodia’s minimum wage will rise to $250, above the current wage floor

in Malaysia – among South-east Asia’s more developed economies. In 2017, Japan’s Artnature, a wigmaker, reportedly sold its Phnom Penh-based factory to a Hong Kong-based firm, citing high labour costs. In 2018, about 10 percent of Cambodia’s garment factories shut down, largely due to external factors including the decline in competitiveness, Loo says. This, coupled with declining productivity on shortened working hours, resulted in a 25 percent drop in production levels that year.

More factory closures, and relocations to cheaper or more efficient manufacturing nations could occur if the pace of wage growth is not reduced, Loo says.

Additional cost increases as a result of EBA tariffs “would undermine the price competitiveness of Cambodia’s garments exports,” says Moody’s Circosta. “Rising costs will reduce Cambodia’s attractiveness as a production base and could weaken foreign direct investment inflows, which have contributed to economic and financial stability,” he added.

GMAC’s Loo says, “troubled times lie ahead” unless the government reduces the pace of wage growth and ensures lower electricity costs. “It would be fatal to assume” that the growth of the garment industry will be sustained at this rate amid declining output levels and surging labour costs, Loo says.

Although, he adds, one potential positive takeaway from the EBA removal is that it could turn out to be the jolt the industry needs to spur officials into action. CapCam