Smart city technology has the real estate sector abuzz, but hurdles remain

For the latest Cambodian Business news, visit Khmer Times Business

When developers break ground on Phnom Penh City Centre later this year the project will mark Cambodia’s first foray into the coming era of smart cities. It is a big step in a country that has yet to build even a smart building.

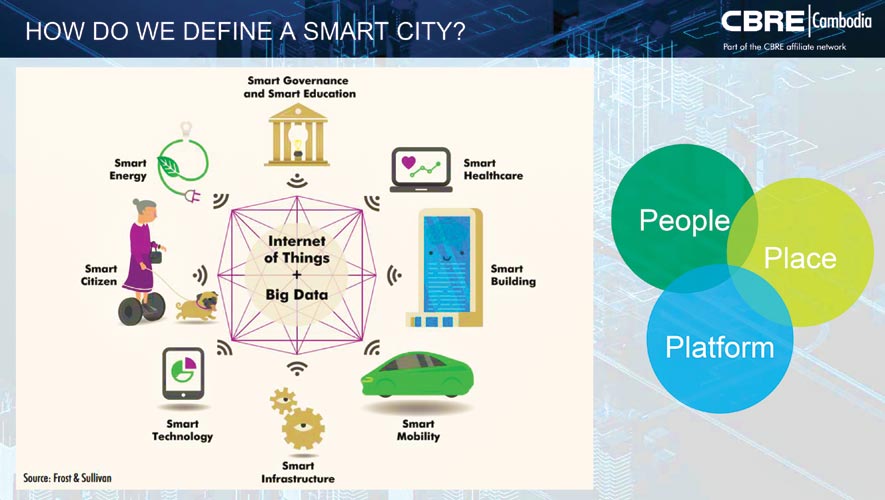

Built on blockchain technology, the satellite city near the Phnom Penh airport will be the first development of its kind in the country to be fully linked through a network of electronic Internet of Things (IoT) sensors to collect data and then use the data to manage assets and resources efficiently. This includes data collected from citizens, devices, and assets that are processed and analysed to monitor and manage traffic, water supply networks, crime detection, waste management, information systems, schools, libraries, hospitals, and other community services.

Smart cities are defined as urban areas that use technology and data to create efficiencies and improve sustainability. Major technological, economic and environmental changes have generated interest in smart cities, including climate change, economic restructuring, the move to online retail and entertainment, urban population growth and pressures on public finance.

“A smart city is built on data flow,” says Eddie Lee, managing partner of Limestone Network Pte Ltd, which uses blockchain technology to build infrastructure for modern cities. According to Limestone, it starts by having a digital ecosystem that allows real-time analysis of living and moving data.

“We are trying to improve the lives of Cambodians,” Lee adds. “There will be a smart city in Phnom Penh,” he says in reference to the Phnom Penh City Centre project, which is still years away from completion.

Cities to be transformed

Three Cambodian cities, Phnom Penh, Battambang, and Siem Reap, have been chosen for smart city transition as part of the Asean Smart Cities Network (ASCN) which aims to synergise smart city development efforts across Asean by facilitating cooperation on smart city development, catalysing bankable projects with the private sector, and securing funding and support from external partners. In all, 26 cities in the 10-nation bloc are participating.

How smart cities might look in Cambodia was the topic of a recent gathering of local business experts who were excited about the idea of smart cities while wary of the challenges ahead and unsure of how to get there. There is also the question of how to fund these projects. Is it the government, the private sector or via public-private partnerships (PPPs)?

“We don’t have the rules in place,” said DFDL Mekong (Cambodia) Co Ltd managing director Guillaume Massin. He is hopeful, however, that the new draft law introduced last week by the Economy and Finance Ministry could go far to clarify how the government will be able to work with the private sector. The proposed law would replace the 2007 Law on Concessions in order to enable more flexible use of different models of PPP. “We have never applied PPPs to large development projects,” Massin says.

Michael Cassagnes, chief executive officer of architecture firm Archetype Cambodia Ltd, says that at the moment there are no incentives to build green buildings. “It would be nice if the government provided some incentives,” he says.

Why are smart cities important?

By 2050, the world’s population is expected to reach 9.8 billion. Nearly 70 percent or 6.7 billion people are expected to live in urban areas. In Cambodia, almost 45 percent of the country will be living in cities. That means the challenges facing modern cities is increasing demand for services and housing, more traffic and pollution, carbon emissions, waste disposal, and resource limitations.

According to James Hodge, associate director at CBRE Cambodia, construction is responsible for 11 percent of global carbon emissions. How cities combat that impact sustainability is becoming increasingly important.

“Phnom Penh is no different than other cities,” Hodge says. “We have problems that need to be addressed.”

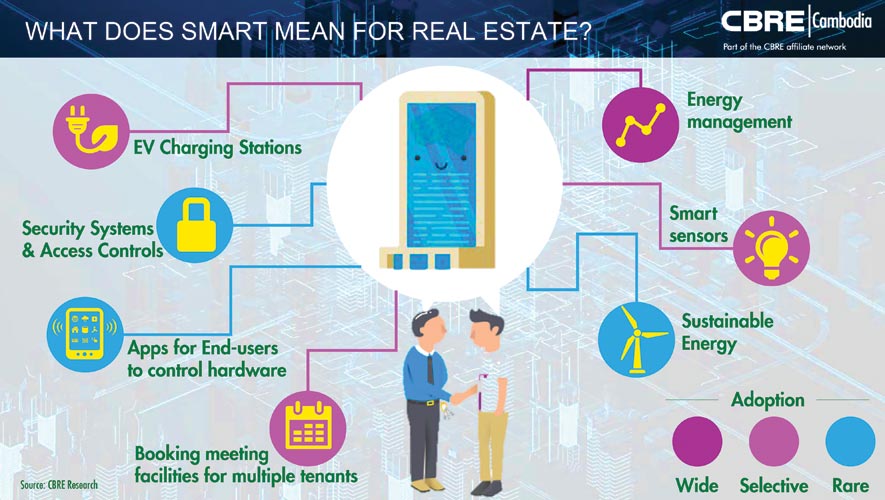

More than 80 percent of landlords expect the rise of smart buildings. According to Hodge, this increase in smart real estate will bring significant economic, environmental, and experiential benefits for them.

On the economic side, landlords will see reduced operating costs, increased tenant demand, and fewer maintenance expenses. Environmental impacts will also be seen with the reduction of energy use. Security and safety will also be improved. The coming of 5G technology will also change the playing field.

“5G is coming,” Archetype’s Cassagnes says. “When it comes it will accelerate smart building with one object talking to another.”

Challenges ahead

While the benefits of smart cities seem clear, challenges remain and there are hurdles to overcome before smart cities take off in Cambodia.

“There is a lot of talk. The biggest challenge is implementation. It is quite complicated,” Hodge says. “In Phnom Penh, we see isolated incidents where smart technology is used, but it’s not connected up,” he adds.

DFDL’s Massin is looking at the numbers. “From the business side it is access to finance,” he says. Lack of regulation is also keeping investors at bay except for Chinese investors. “If you want investment you have to have the rules in place,” Massin says.

Seng Vannak, administration director at Phnom Penh City Hall says the biggest challenge for the city is that people understand the development. “We can create the plans, but we need people to understand. That is the challenge for the government — how to connect the city with a network”

Iwase Hideaki, a project formulation advisor at the Japan International Cooperation Agency, says all those factors mean a smart future might take a while. “There is a long way to go for Cambodia to see a smart city,” Hideaki says.