While the last remaining Japanese aid shrinks, Cambodia must now look at ways to persevere with grit and sweat to stand on its own feet, at long last

For the latest Cambodian Business news, visit Khmer Times Business

Japanese aid that built Cambodia’s infrastructure for the past 29 years will shrink to about four percent by 2025 as the Southeast Asian country records sustainable annual economic growth. Financial aid from Japan would be replaced by yen credit and foreign direct investment (FDI) instead.

“In the near future, the grant landscape would change in Cambodia because grants are reducing as the economy develops. The government should consider loans from Japan,” says Hori Kohei, second secretary of the Embassy of Japan in Cambodia. Kohei is in charge of the Economic and Official Development Assistance (ODA) section.

Cambodia has been reconstructing the nation after two decades of civil war and political turmoil. Japan has been implementing the ODA scheme made up of loans, grant and technical cooperation in Cambodia since 1991, contributing to Cambodia’s nation reconstruction and peacebuilding.

Kohei says that 20 years ago, 25 percent of ODA was used for developing activities in Cambodia but the aid has been decreasing progressively, although private sector involvement and FDIs have risen.

As of 2017, ODA disbursements to Cambodia amounted to $1.28 billion loan, $1.83 billion grant, and $784 million technical cooperation assistance, according to the Japanese embassy.

In 2017 alone, Japan gave out loans totalling $213 million, up 112.36 percent from $100.3 million in 2016. Grants dropped 60.7 percent to $38 million from $96.7 million in 2016, and technical cooperation dipped to $32 million from $35 million in 2016.

The grant aid and technical cooperation have been pillars of Japanese assistance, and its active cooperation made it one of the largest donor countries in Cambodia.

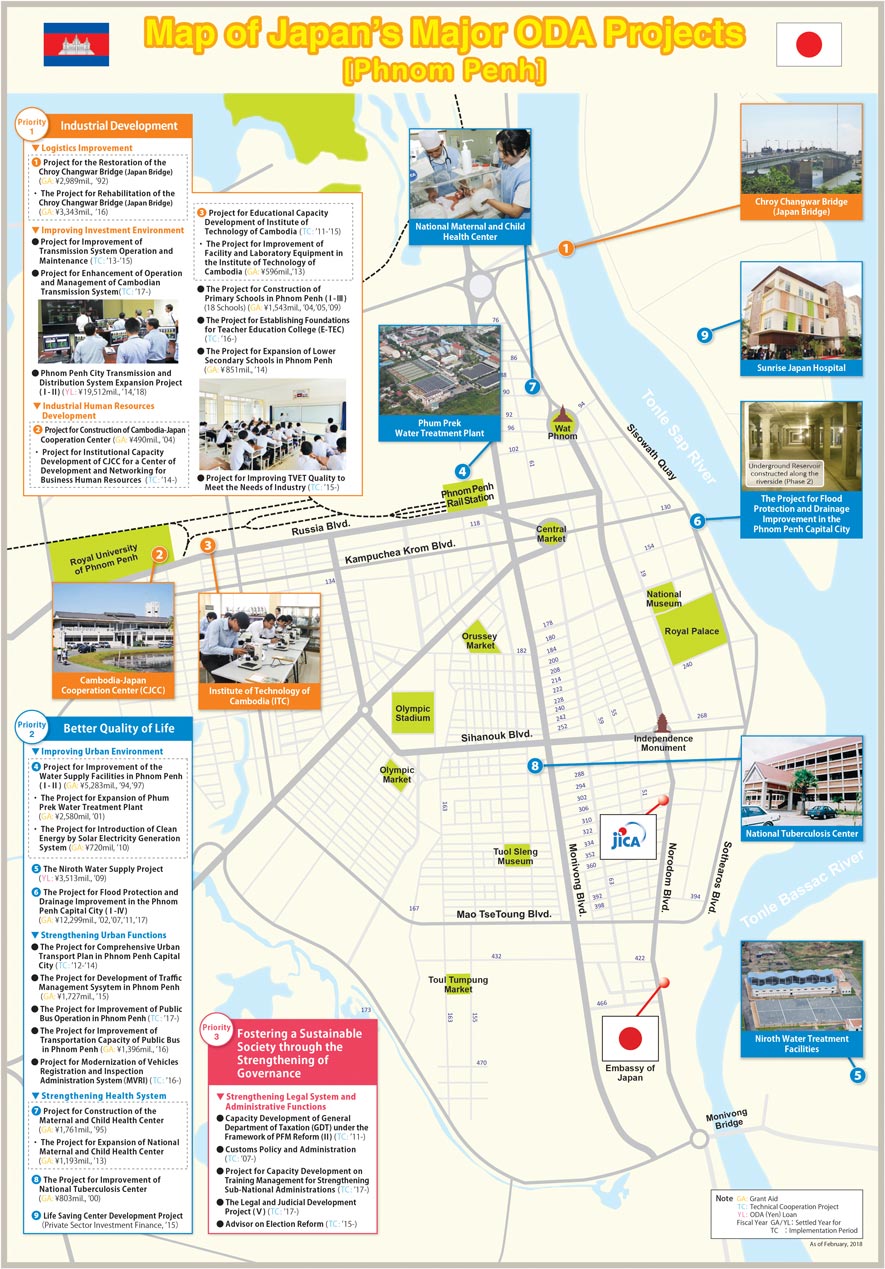

The aid focusses on three priority areas. It includes industrial development, and promotion of regional connectivity such as the development of the Southern Economic Corridor and Sihanoukville Port, construction of Tsubasa Bridge, and the provision of buses to reduce traffic congestion.

It also concentrates on better quality of life by developing teaching colleges, and demining activities while fostering a sustainable society through governance. This involves empowering the legal system and election reform by providing ballot boxes.

Kohei says the Japanese government understands that Cambodia is promoting public private partnerships (PPPs) where a synergy between that and ODA investments can ensure a more effective, and efficient outcome.

“What I want to say is that the role of ODA is changing, so our Japanese ODA system has to change. As the future changes, the Cambodian government would have to resort to loans from Japan,” he states.

According to the Cambodian Economy and Finance Ministry’s Public Debt Statistical-Bulletin, up to 2018, the Kingdom disbursed $7.31 billion from public domestic and external debt out of a total loan of $11.39 billion. Of that total, Cambodia borrowed $1.34 billion in 2018, which is 11.81 percent of the borrowing.

Low loan interest rates

Japan’s ODA loans support developing countries by providing low-interest, long-term concessional funds to finance their development efforts.

For Cambodia, Japan offers a 0.01 percent interest rate and 40-year repayment period including a 10-year grace period.

However, Kohei adds that Japan has to create a new structure or innovative idea to merge private investment and ODA.

If the Cambodian government requests for funds for highway construction, and they do not want to borrow the whole sum from Japan, which then becomes a concessional loan, it can seek private sector investment.

Here is where the Japanese side would need to consider providing a concessional loan via private investment.

“The Cambodian government wants PPPs rather than concessional loans, and they want more grants. However, grants from Japan are now predominantly concessional loans and technical cooperations,” Kohei explains.

Japanese FDIs

Assistance to Cambodia would lead to redressing intra-Asean disparities, which is crucial for the bloc’s development.

The relationship between Japan and Cambodia has been growing through tourism, FDIs and knowledge sharing in the political field.

Japan regards its active contribution to Cambodia’s reconstruction and peacebuilding as its own goal to establish a successful model in the process of peace.

According to Japan Business Association in Cambodia (JBAC), Japanese companies, some 260 of them as of 2018, are present in manufacturing, construction, finance, and retail sectors.

Direct investment by Japanese firms in the tourism sector including hotels amounted to $882 million in 2018 while $63 million was invested in auto parts, garment, and expansion of existing factories in 2017, states the embassy.

Socio-economic development

Japan supports the strengthening of socio-economic foundation in Cambodia to achieve an upper-middle income status by 2030, says Tomohiro Kanata, first secretary of the embassy.

Apart from that, Kanata says as part of the ODA, work on building the flooding protection system and sewage system in Phnom Penh city has started.

But Cambodia faces a new challenge of urbanisation, and the disparity between urban and rural living. Hence, Japan’s continued cooperation in the development policy with the Cambodian government.

“We believe Japanese investment, such as Aeon Mall has been bringing positive changes to the Cambodian lifestyle. Japanese investors believe that it is important to create jobs and foster human resources in Cambodia, which has positive effects in the local economy,” Kanata says.

Push for better investment conditions

However, issues still plague the cost of doing business in Cambodia where Kanata opines that although companies are interested in investing here, electricity tariffs and logistic costs are higher than neighbouring countries.

While he lauds the improvement in investment policies implemented by Prime Minister Hun Sen which has somewhat addressed cost issues, he hopes further efforts to better the investment climate would lead to increased investment in Cambodia by Japanese companies.

Mey Kalyan,senior advisor to the Supreme National Economic Council, acknowledges that Japanese grants are reducing in line with Cambodia’s economic expansion.

“Japan focusses on capacity building now, which is its core element. It is working on infrastructure, economic development, culture and better living standards, apart from human resource growth,” he says.

But Kalyan says that Cambodia must create an investment-friendly environment to attract Japanese investors to Cambodia where the latter can benefit from technical know-how.

Cambodia should take advantage of its relationship with Japan by attracting existing Japanese companies in Asean countries to set up factories here, he says.

He is aware of the high logistic cost which he claims resulted in a slow down in investment from Japan that has somewhat dampened Cambodia’s aim to increase its competency.

Kalyan cites an example of a Japanese company in Phnom Penh Special Economic Zone which was affected by business costs including logistic costs, cross-border procedures, taxation, customs, and electricity tariffs.

“I was told that it costs them $115 for logistics and electricity but the cost of doing business in Thailand is $100. If we can reduce the cost to $80, we can attract more Japanese investors,” Kalyan adds.

“We all know that hard infrastructure such as roads, and electricity will not be resolved overnight. However, we can solve logistic issues,” he adds.