Scenes of absolute devastation reached the world from Australia this week as bushfires ripped through New South Wales killing three people and destroying more than 300 homes. Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, the UK is experiencing some of the worst flooding it’s seen in years.

For the latest Cambodian Business news, visit Khmer Times Business

Closer to home, just this month The New York Times published remodelled data showing the changes in rising sea levels by 2050.

The results paint a bleak picture for Southeast Asia, with much of southern Vietnam predicted to be under water in just 30 years.

But beyond the impending climate catastrophe that world leaders appear to be slumbering over – both here and the world over, the fabric of society stretches thin and frays at the edges. Inequality widens, ever further divisive politics stem from issues pertaining to wealth, race, gender and power, but to what extent are things getting worse and to what extent are we simply more aware of these issues?

Well for the most part things are intensifying. Time is running out to alter the course of humanity’s trajectory into the abyss of a deteriorating environment, but our enhanced awareness and access to information about this is key to addressing it.

This is one of the underlying reasons for what has been observed as a global shift from classical venture capitalism to so-called impact investing. These may sound like slippery phrases that cloak the world’s wealthiest in a veneer of philanthropy, but they signal a more enlightened approach to investments.

Private sector approaches

“I think the easiest definition to understand this is that a company or a venture can have a double bottom line, so that you want to make a return for your shareholders – it’s a profit-making company, not a charity, it’s the opposite – it’s for profit, but you also want to have a positive social return,” explains Nick Beresford, Resident Representative of the UN Development Programme (UNDP) in Cambodia.

Beresford and his team have recently been expanding the horizons of the UNDP, recently choosing to utilise and mobilise private sector resources to further the objectives of social development in Cambodia. This resulted in a UNDP partnership with ride-hailing giant Grab, who – in conjunction with the Ministry of Public Works and Transport – is working to reduce road deaths in the Kingdom and both are currently studying means of increasing safety for drivers.

“More Cambodian people lose their lives through traffic accidents than through HIV/AIDS, so we need to tackle these new problems and we very much welcome private sector companies who want to put their money into doing this. Why do they do this? It’s because the owners and their shareholders are motivated for the same reasons we are – they just want to see better outcomes and they can see the way that their businesses can contribute to it,” explains Beresford.

The attraction of Cambodia

In 2018, the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) published a comprehensive analytical study entitled “The Landscape for Impact Investing in Southeast Asia”. Covering 514 impact investment deals across 100 stakeholders between 2007 and 2017, GIIN’s study found a growing potential within the region.

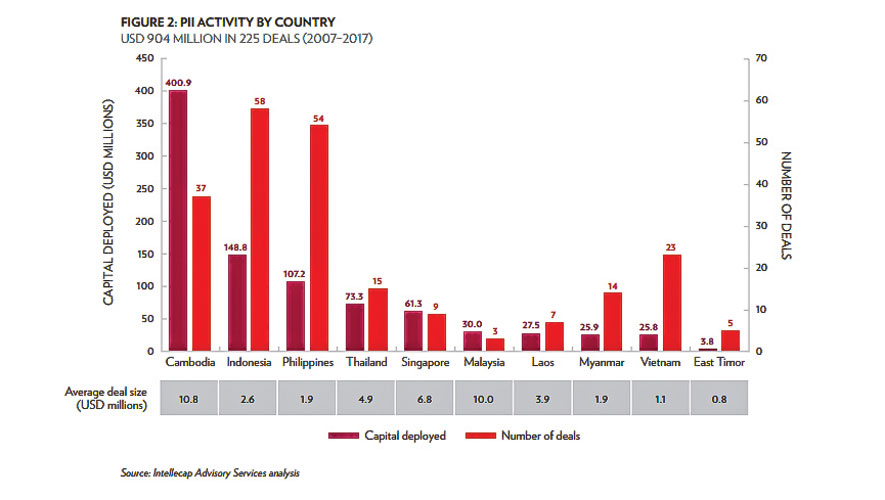

Over the course of the decade analysed, the study found $904 million deployed to Southeast Asia spread across 225 deals made by private impact investors and $11.2 billion deployed over 289 impact deals done through development financial institutions.

Through GIIN’s Annual Impact Investor Survey, it found that almost one third of respondents were already investing in Southeast Asia and of those that were, 44 percent were planning to expand their investments in the region.

Within the region, the study found that Cambodia – by a long way – took the lion’s share of private impact investor capital, garnering some $400.9 million across 37 deals. Out of the 11 countries analysed by GIIN, Indonesia attracted the next largest amount of private impact investor capital, with just $148.8 million over the same 10-year period. Private impact investors deployed almost as much capital in Cambodia as Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam combined – chiefly, the study suggests, because of the Kingdom’s open, dollarised economy.

“The mantra of development in the 21st century is no longer: ‘Funding Development’ but rather ‘Financing Development’ – thus, the need to enrol private sector into strategic partnership to help finance such activities,” says David Van, executive director of Deewee Management Consultants and a long-time proponent of public-private partnerships.

Van recognises the increased traction that impact investing is gaining, particularly in this region, but doesn’t expect it to replace venture capitalism anytime soon. He goes on to note that while venture capitalists typically expect to see quick returns on their investments, impact investors tend to be more patient.

Investment return

“Impact investment puts a strong emphasis on social impact criteria such as environmental benefits, improving the livelihood of farmers, renewable energy, developing the circular economy concept etc.Impact Investors usually take only minority equity to have a director seat on the board of the loan recipient firm and they are accompanying the firm for usually five to 10 years or slightly more to ensure all social impact criteria are fully met in the business model of the firm they invested in,” says Van.

This, he believes, forms part of the changing face of international development.

“The mantra of development in the 21st century is no longer ‘Funding Development’ but rather ‘Financing Development’ – thus, the need to enrol the private sector into strategic partnerships to help finance such activities,” he says, citing the UNDP’s utilisation of PPPs from 2018 – which he sees as an example of what is known as blended finance.

According to Van, impact investing funds are valued at billions across the world, with even large commercial banks developing their own impact investment divisions to source bankable projects that guarantee a strong social impact. The need for blended finance or impact investing stems from the growing value of sustainability, as Beresford points out.

“We often talk about sustainability, but what happens when the donor money runs out? Does the programme just end? How do we make sure it goes forward? A great way to make sure the programme goes forward is if someone’s making money from that activity going forward and so encouraging the private sector to be more involved in issues that interest them – issues that have social and environmental beneficial impacts have a lot of potential, I think, in terms of sustainable programmes that last and continue to provide benefits,” he says, responding to criticism of the UN’s appropriation of funds.

“People often say, look at all this money the UN has. Why don’t we just give it directly to the poor. There’s no lasting benefit to this. I’m sorry – cash transfer programmes can work, but in countries that have good social systems and have lots of other benefits that allow the cash transfer to work in conjunction with other programmes, not just on its own,” says Beresford.

Ok boomer

With Cambodia’s overseas direct aid drying up as the country grows economically, the need for innovative new models of development have become apparent through the gaping holes in national infrastructure and the changing needs of the population. This is, of course, all compounded by the impending impact of climate change – which is expected to hit Cambodia and indeed the region especially hard because of a lack of preparedness.

This is in part, the driving force behind impact investing but, for Beresford, the growth of the socially conscious capitalist movement can be seen through the lens of age.

“Younger people are better educated all over the world – that’s not a criticism of older people, it’s just a fact that as we have become wealthier, on average in most countries, we have seen more educational opportunities opening up,” he argues, noting that this is just as true in lower-income countries such as Cambodia as it is in higher-income countries around the world.

“Those people are far more likely to understand climate change, environmental effects, issues to do with inclusion, other social issues, but they’re far more likely – when they consume and when they look at products and services and when they buy in as a consumer, as a producer, as an investor and so on – to bring that in and so I think that’s another issue that stems from generations and education,” says Beresford.

However, as Beresford notes – Cambodia is not yet in the position to fully enjoy the benefits that many impact investors could bring. Much of the deals done in the Kingdom have been focused on microfinance institutions (MFIs) which ostensibly aim to lift people out of poverty, but have been accused of increasingly displaying predatory tendencies that trap impoverished Cambodians in cyclical, systemic poverty.

No picnic for impact investing

This was highlighted in a recent but criticised study by the Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (LICADHO) that said it found some 2.1 million Cambodians collectively owed approximately $8 million in MFI debt.

The Hun Sen administration has denounced the study, claiming it wasn’t reflective of the country given the small batch of case studies, however the majority of experts argue that a wider study would likely see similar results.

Early years

“I think it’s kind of early years. Our economy’s still quite small and it’s growing fast, but it’s a relatively small country as well, so the absorbative capacity for large amounts of institutional investment is limited and that does create somewhat of an issue,” explains Beresford, who sees a mismatch between the scale of funds from impact investors and bankable projects in the Kingdom.

Whether or not impact investing is set to be the future of international development is uncertain, nor can it be said that all venture capitalists will open their hearts and wallets to the socially conscious nature of the practice, but the continued growth of impact investing holds potential for Cambodia’s development.

Beresford, who hopes to see the development world adopt a little more of the risk-taking approaches to financing projects seen in the private sector, remains cautiously optimistic.

“I’m always cautious that we don’t overhype these things. As soon as we start to say that this is the answer, then I think we’re probably onto something that isn’t the answer, but I think it’s definitely a positive part of the way that we can approach development problems.”