Concern over 30 percent predicted rise by year’s end

For the latest Cambodian Business news, visit Khmer Times Business

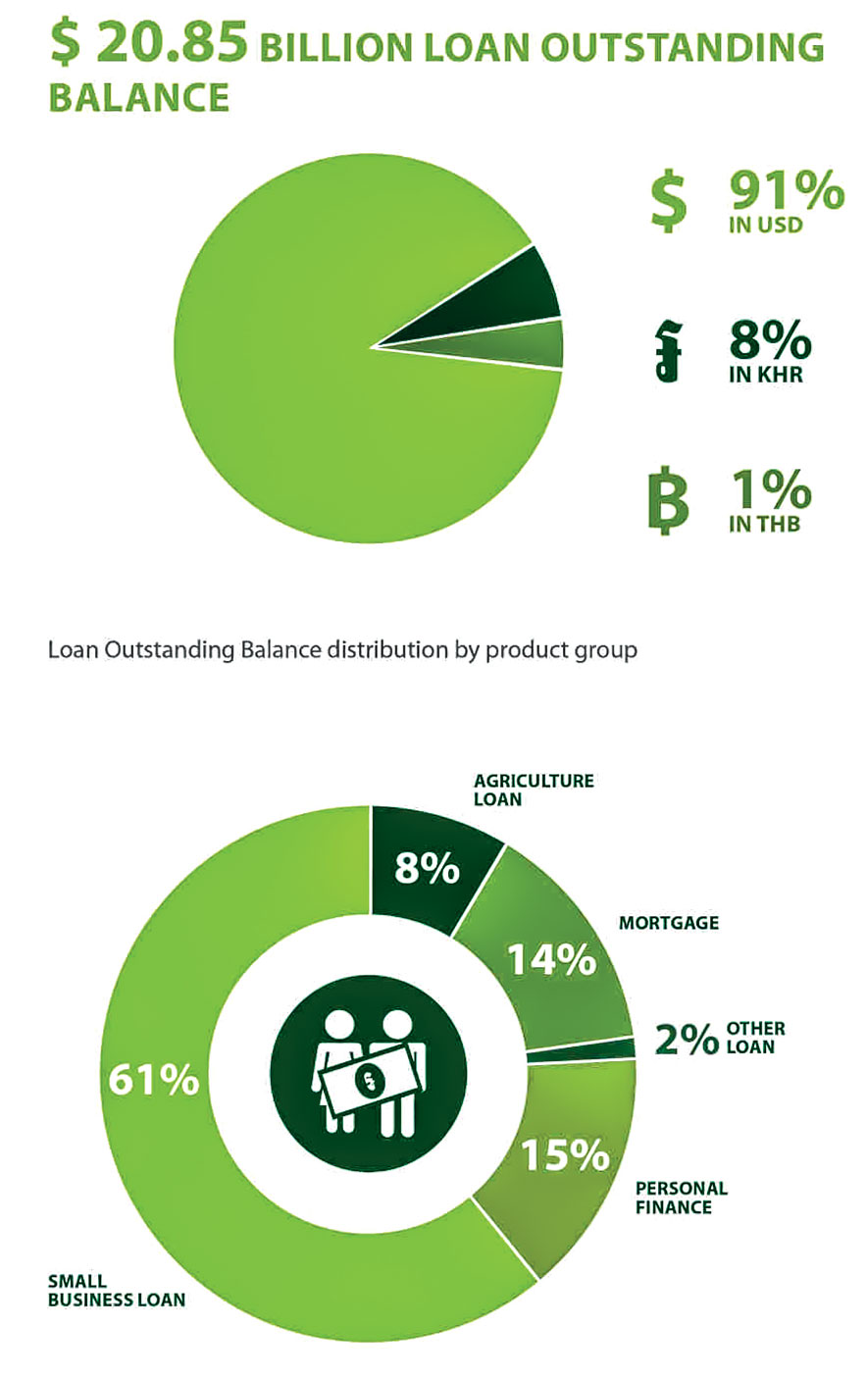

The total outstanding balance of loans in the Kingdom jumped from $20.84 billion at the end of 2018 to approximately $23 billion at the second quarter of this year and is predicted to grow around 30 percent in total by the end of 2019, according to Credit Bureau Cambodia (CBC).

“The outstanding balance as of June 2019, is $23 billion,” says Oeur Sothearoath, chief executive officer of CBC, who is now in his sixth year at the bureau. According to the CBC’s annual report, there are currently 3.2 million active borrowers in the Kingdom.

“So this is not the new loan disbursement between those two quarters. Some loans, for example, a mortgage, might last 10 years, so those people who took out loans in the last five years still have an outstanding balance which is captured in this figure too, so it’s a combination of both existing loans and new loans,” he explains.

Mortgages however, made up just 14 percent of the Kingdom’s outstanding balance, reaching $3.42 billion by the end of the second quarter of this year – up 30 percent from the same period last year. The Asian Development Bank and the National Bank of Cambodia (NBC) have both expressed concern over this rise and its potential impact on economic growth.

The rest of Cambodia’s credit looks stable, with 15 percent being attributed to finance, 8 percent to agriculture and just 1 percent to credit cards.

“I can say that the credit card penetration in Cambodia is still low here, for two reasons. The first one is the [lack of] public interest in holding a credit card [and therefore being banked] and the second one is the credit card providers… contribute around [just] $50 million to the outstanding balance,” notes Oeur.

The majority of that balance – 61 percent according to CBC’s 2018 annual report – was accounted for by small business loans.

“We are using the term small business loan – we don’t use the term SME [small and medium enterprise] – because, from our perspective, a small business loan is particularly for a business purpose, whether it is for growth, for construction, for working capital, for asset financing.

“Depending on the bank and microfinance – if you run a grocery store, for example, and then you go to a micro finance institution (MFI) to get that $10,000 loan to improve your store, this comes under working capital financing, so that is part of our small business loan.”

Eager to stress the accomplishments of CBC, Oeur pointed out that since the bureau’s inception, Cambodia has improved vastly in terms of providing access to finance. He points out that in the World Bank’s annual Doing Business report – an analysis of 190 countries – Cambodia has gone from 98th place in the report’s “Getting Credit” category in 2012, to 52nd in 2013.

It currently stands at 22nd place out of 190 for access to credit, but remains 185th for starting a business, 182nd for enforcing contracts and 137th for paying taxes.

Oeur says he is actively trying to expand the data sources available to CBC in order to further provide finance to Cambodians – in particular those with no credit history, whom he suggests account for 15 percent of new loan applications.

“Currently, in the credit reporting, we have around 6 million consumers in our database. Sometimes first-time borrowers might not have credit histories, but they exist on other platforms. For example, those people might have utilities histories, they might have water bills, they might have electricity bills,” says Oeur, who believes that with shared data from utilities companies, CBC could help grant more access to finance across the Kingdom.

Debt has become a sensitive issue for the Hun Sen administration, with numerous international organisations warning of an alleged debt-trap following huge Chinese investments across the Kingdom.

This was compounded by the rising debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratio that some feared would hamstring the country in the long-run, despite projections from the NBC predicting GDP growth for 2019 to hover around the 7 percent mark. The World Bank’s economic outlook released this month pegged GDP growth at 7 percent for 2019, but falling to 6.8 percent for 2020 and 2021.

More recently, two nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) working in Cambodia presented a joint report condemning, what it saw as, predatory lending practices. Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defence of Human Rights (LICADHO) and Sahmakum Teang Tnaut in August this year revealed figures claiming to highlight potential abuse within the microfinance industry.

The report however has been widely decried by the government and financial organisations, who were chiefly concerned with the methodology. The study found that $8 billion in microloans was owed by some 2.1 million Cambodians and pointed to predatory, profit-driven elements within the microfinance industry, however the government argues that sampling 28 cases from 10 provinces across the country is not enough for the study to be conclusive.

“If you access the report, you will see that it’s not a scientific report and when we say scientific report, we mean that the two NGOs need to disclose, how they select the sample, what does the sampling frame look like, but if you look at the report, by reporting standards it is not scientific – and it is not a quantitative study, it’s a qualitative study,” argues Oeur.

“Results from qualitative research is just supporting evidence only. You can generalise about the impact of microfinance from there, but I am sure that there is still a lot of questioning to be done on their part,” he adds.

In a February 2019 policy note, the World Bank weighed in on the growth of MFIs in Cambodia, noting the potential for positive change and serious risk.

“Risks are increasing for MFIs and for the Cambodian economy in general, partly reflecting looser lending practices,” the note reads. “Over the past five years, the average loan size increased more than 10-fold, as did the share of loans for consumption needs and the portfolio-at-risk. These trends are due to a combination of the low penetration of financial instruments, deteriorating lending practices and low financial literacy.”

Despite having brought positive financial and welfare benefits to households, the World Bank policy note reports that more needs to be done to safely increase access to finance, while mitigating the potential pitfalls inherent to MFIs.

Beyond the reports from LICADHO and Sahmakum Teang Tnaut, Oeur reveals the CBC is currently conducting its own studies into lending practices across the Kingdom.

“Currently, we are just starting two research projects. CBC, CMA [Cambodia Microfinance Association] and JICA [Japan International Cooperation Agency] will kick off the research project on the impact of interest rate caps. This will be scientific research. We will interview around 800 families across the country,” he says.

The aim of the study is to establish whether or not the 2017 memorandum of understanding (MOU) signed by the CMA to cap interest rates at 18 percent has been effective at slowing the growth of the sector. Specifically, Oeur wants to find out how borrowers have been affected and what it has meant for the financial institutions, because the World Bank note claims that numerous MFIs have offset losses from capped interest rates with the introduction of new fees.

“If you understand the Cambodian funding structure, most of the MFIs get loans from abroad – from the EU, from the US or another country. On average, these investors charge an interest rate of 8 percent. That’s why the cost of funds is already high and you need to consider your operational costs as well.”

The other research project – a joint investigation by CBC and CMA – will focus on lending guidelines in an attempt to further understand the issues facing high-risk customers.

“Since December 2016, the lending guidelines MOU has been a self-selected mechanism aiming to slow down the growth of the sector. A lot of international organisations are saying that in Cambodia the credit growth is too high, which has previously been around 40 percent, 30 percent as of the last two years,” says Oeur.

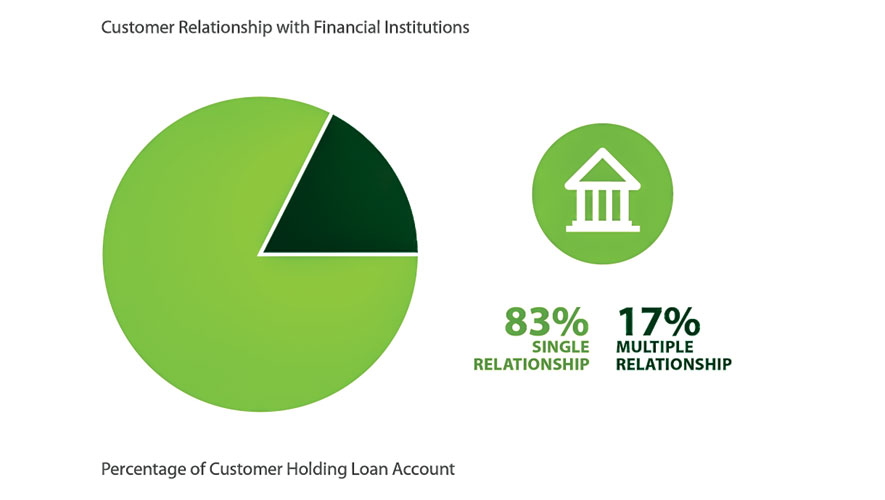

The MOU on lending guidelines saw CMA members agree to deny loan applications to any borrower who already have two relationships with MFIs. This was in a bid to curb the risks of refinancing – a practice in which borrowers take out secondary loans to pay off existing debts.

“We are saying that the refinancing – sometimes – is not bad, but you need to know whether it is a low risk, moderate risk or high-risk – and what we are trying to observe is the refinancing that is classified as high risk,” he adds, suggesting that through better understanding of the problems facing high-risk customers, regulators are better poised to aid them.

Oeur explains that just 5 percent of new borrowers are classified as high-risk, but hopes that the study – which CBC and CMA will undertake this month – will shed more light on the elements involved.