Fear of taxation, and poor bookkeeping practices could spell doom for family-owned enterprises as Cambodia moves up the value chain

For the latest Cambodian Business news, visit Khmer Times Business

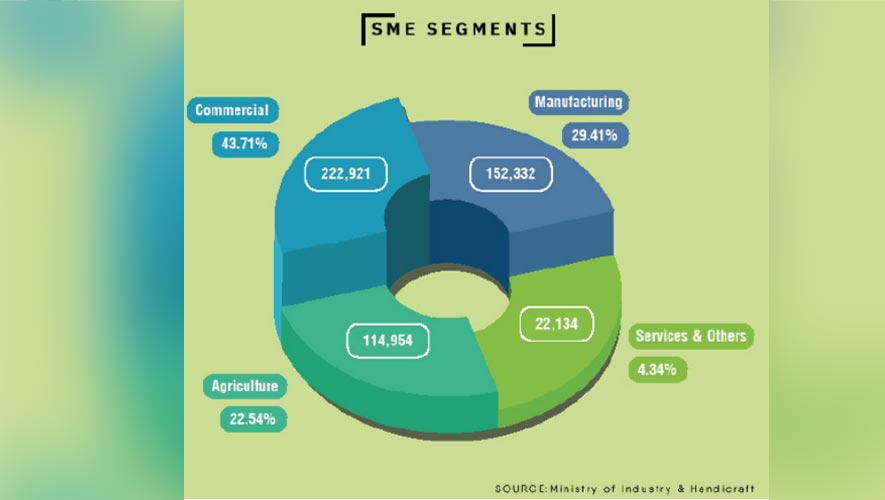

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are the backbone of most emerging economies. Cambodia is no exception. Out of 510,000 enterprises, 40 percent are involved in commercial (retail) trade, 30 percent are industry and manufacturing-based (mostly food and beverage), 22 percent (agriculture), eight percent services and others.

As for micro SMEs, 83 percent to 86 percent of 150,000 businesses are involved in handicraft and micro trades, nine percent or 20,000 enterprises are small and medium manufacturing, and less than one percent (2,000 factories registered) are medium-sized manufacturers.

The SME sector contributes 58 percent to the gross domestic product and employs 3.5 million to four million people or 70 percent of the labour market.

Small businesses in Cambodia looking to export face many challenges because they do not have scale, says Allen Dodgson Tan, an American-Cambodian entrepreneur.

The picture is different in Thailand where SMEs flourish with a bigger support network and small businesses get promotional aid from the government and associations.

“For larger companies to reach bigger markets, they need the consolidators (government and industry p[ayers) to push them up,” he adds.

However, a majority of MSMEs, which are family-owned, suffer from low technical management and financial expertise, and unskilled labour.

This is compounded by lack of access to government funds or private aid, and high microfinance interest rates, and inadequate collaterals. If the challenges remain unsolved, the industry might find it difficult to remain sustainable.

The fear of the unknown

But the common theme surrounding SMEs is the formalisation of their businesses.

Tan believes that many Cambodians are wary about digitising their accounts and money. The lack of understanding stems from misplaced fear, and the absence of social contracts between businesses and the government.

“It’s a problem that needs to be addressed by the General Department of Tax as many think they will be taxed unfairly,” Tan says. He opines that more dialogues need to take place between the government and business owners.

The absence of proper bookkeeping hinders micro-enterprises from securing loans to expand business or acquire new technology. Similarly, the government is not able to support these enterprises unless they register and maintain accounting records for audited.

Laim Kimleng, undersecretary for the Handicraft and Industry Ministry, says that most of the SMEs in Cambodia are family-owned businesses and do not keep proper accounts.

Kimleng adds that for the moment, MSMEs that do not keep proper accounting records, need not report to the ministry since they are small.However, the ministry is providing training on how to do bookkeeping.

SMEs in the export sector

According to the Federation of SMEs, export-oriented SMEs account for 10 percent only, revealing a significant absence of locally-manufactured products overseas.

SMEs manufacture products including food and beverage, tobacco, furniture, plastics and souvenirs, valued at $9.3 billion a year but it is not even adequate to supply the local market.

“Local products from the manufacturing sector amount to only nine to 10 percent of the export segment while the agriculture sector such as rice, rubber and cashew accounts for over 30 percent. These two segments are the ones that support the export market,” Kimleng says.

In the meantime, the Department of SMEs is considering reducing the export of raw materials from the agriculture sector and raising the export of finished products.

“The raw material will instead be used for local supply. We will push for this,” says Kimleng who is the director-general for the Department of SMEs. He adds that this would boost the national economy.

“We should strengthen the ability of agri-processing to increase finished products. We know that some of our end-products are not on par with that of other countries. As such, we need to expand production chains in the manufacturing sector,” he says.

Leang Leng, managing director of Leang Leng Fish Sauce Enterprise, which employs about 60 workers, tells Capital Cambodia that transforming from a family-owned business to becoming compliant to the law was initially a struggle.

The company started operations six years ago and became fully compliant in 2017. “Our sales has surged to 8,000 bottles from 800 in 2017 because of the trust we gained after fully complying with the tax law, regulations and food safety and standards,” Leng says.

Some family-owned businesses are reluctant to adhere to the law as they fear being taxed or having to be transparent with their financials.

Managing Director

Leang Leng Fish Sauce Ent

“I am concerned over the number of unregistered SMEs, whom are our competitors, since they do not pay taxes. We are also unsure of their adoption of safety and standard practices on products,” he says.

For now, there is no requirement to send annual income statements and balance sheets to the ministry. But they are required to send to GDT.

Leng also notes that some SMEs are not aware or understand the government’s directives or prakas, so they lag behind the laws or regulations.

Developing policies and partnerships

“We have direct and indirect policies. The Industrial Development Program (2015-2025) supports the SMEs,” Kimleng says. Other policies include “One Village, One Product”, and “Green Practice”.

Kimleng says his department has drafted SME policies stemming from the IDP, which they plan to implement to strengthen, expand and facilitate the transition of SMEs into Industry 4.0.

“The Asian Development Bank and the Japan International Cooperation Agency have come together to draft SME policies together with ours,” he adds.

Once the draft is completed, the SME department will submit it to the inter-ministry and the council ministers for approval. The ministry also plans to initiate aids via partnerships. For instance, Smart Axiata Co Ltd has set up the Digital Innovation Fund which aims to provide financial assistance to startups in the tech sector.

“We need to stop thinking of startups as pure tech startups, many startups often present solutions that interact with real life issues,” Tan says.

SME clusters

Both Kimleng and Tan agree on the concept of SME cluster, where similar SMEs support each other. This way, the ministry can help in terms of technical aid, quality control, and infrastructure.

Initiatives such as agricultural “SME cluster” by Worldbridge Group and enhanced co-working spaces like The Factory Phnom Penh are a step forward.

Kimleng believes that by clustering similar businesses, quality and quantity are assured.